14

Dr. Strangelove, or: How I stopped worrying and learned to love a brain parasite.

Oct 09, 2013

3591 views

International travel, huge media frenzies, and mind-control parasites. When I left the University of Arizona, diploma proudly in hand, I had no idea that a mere 5 years later these things would be my reality. I am currently in the 5th year of my PhD graduate program in Molecular and Cell Biology at the University of California, Berkeley. After studying protein evolution for 4 years in undergrad, I knew without a doubt that I wanted to continue research for the rest of my life. I applied to the top graduate programs in Biochemistry and rejoiced when I was accepted into UC Berkeley’s prestigious program. My interview with the renowned biochemist and current president of Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Robert Tjian, solidified my interest in cutting edge biochemical research (specifically in his lab). Following an arduous but enthralling rotation in his lab, I decided to take advantage of the ‘umbrella’ Molecular and Cell Biology program that I found myself in and explore Genetics and Immunology labs, both subjects I had little to no previous exposure to. That’s when things got weird.

Near the end of my third rotation studying the immune response to a parasitic brain infection, I stumbled upon research suggesting that Toxoplasma gondii, the subject of my impulsive departure from biochemistry research, could cause mice to lose their fear of cats. Cats are the primary host of this parasite and require intermediate hosts such as mice to be eaten by cats in order to complete its life cycle. This research suggested that the tiny single-celled parasite had evolved a way to specifically alter the innate hard-wired aversion that rodents had to cats for its own benefit. I honestly couldn’t believe it. While the studies seemed to be designed well and the results looked pretty solid, there were a lot of questions left unanswered. My curiosity got the best of me and I designed a thesis project to answer the question, ‘If this parasite causes loss of aversion to cats in mice, what is the mechanism by which it accomplishes this?’ Somehow I convinced both the Genetics and Immunology professors that I had rotated with to co-mentor me in this bizarre behavioral, comparative genomics, neuro-immunology, and infectious disease project.

Little did I know that pursuing this particular project investigating microbial manipulation would lead to an international presence. A year after I began studying Toxoplasma gondii, I attended the International Congress on Toxoplasmosis in Ottawa, Canada. There I met a fantastic set of researchers from every discipline (biochemistry, cell biology, immunology, genetics, genomics, veterinary medicine, epidemiology, parasitology, microbiology) with two things in common: they all studied Toxoplasma and they all LOVED to collaborate. Next, I applied to an (all expenses paid) intensive weeklong Biology of Parasitism course in Brazil. I was amazed to discover that there were so many varieties of parasites and also how much information these tiny little ‘passengers’ know about our biology. Finally, two years after presenting my ‘plan’ of how I was going to pursue the mechanism of behavioral manipulation by Toxoplasma, I returned to the same Toxoplasmosis conference, this time in Oxford, England, with a vengeance. While I hadn’t sussed out the precise mechanism, my unconventional interdisciplinary approach led to a surprising discovery that even if the host is able to clear the parasitic infection, the behavior change remains behind.

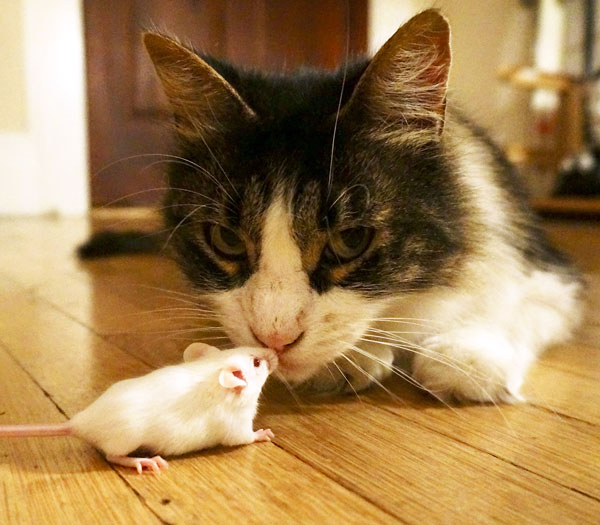

As all graduate students do when they have a ‘story,’ I wrote up my findings and submitted a manuscript to the open access journal PLoS ONE. The typical peer review process followed, but then once my paper was accepted, I received one additional email that was quite different. The journal wanted to promote my work in a Press Release and asked for a couple of quotes as well as any relevant fun photos. Following a quick chat with one of my mentors, I decided to set up a little photo shoot with a friend’s cat and a mouse purchased from a feeder store. The cat was well behaved and the mouse was fool-hardy (or just bred to be unreasonably docile) resulting in a darling set of photos including the mouse on top of the cat’s head. While pleased with myself and the amateur photos, I sent these off to the publisher with little expectation. A week later, I was shocked to receive an email from a Greek reporter wanting to discuss my research, but this was only the beginning. In the following two weeks, over 50 reporters from all over the world were emailing me questions, calling to interview me, setting up radio interviews, and writing up reports on my research. The BBC, Nature News, The Smithsonian, Scientific American, and National Geographic…the list goes on and on. As it stands, the most impressive and humbling aspect of this media attention, though, is the fact that in the course of three weeks, almost 12,000 people have viewed my original publication on PLoS ONE’s website (they keep track). I can only assume that just a fraction of those views are by scientists. While basic scientific research is my love, my bread and butter, I am also deeply passionate about encouraging public interest in real science. Without even realizing it, this media frenzy allowed me to reach thousands of people who may never have seen a primary research article before.

Copyright: © 2013 Wendy Ingram. The above content is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

If you find this essay offensive or in violation of your rights, please email to [email protected]

COMMENTS